Mestre Valentim Fountain

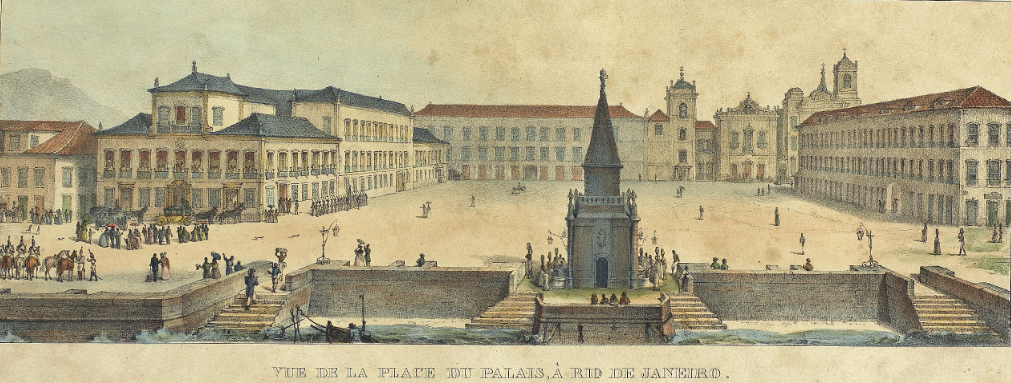

In the mid-19th century, few places in Rio de Janeiro were as bustling as the Pyramid Fountain or the Mestre Valentim Fountain, as it is more commonly known today. Its strategic position on the edge of the docks made it a true hub for meetings, conversations and commercial activities. At night, the location transformed into a stage for plans and conspiracies, as was the case with the Conjuração Carioca. There was an intense coming and going, and a buzz of street vendors, enslaved laborers who were allowed to do odd jobs, civil servants, sailors who had just arrived, were stationed or were departing, travelling salesmen, drovers, small and wealthy merchants, soldiers and ministers.

The is how the French artist Jean-Baptiste Debret, who was largely responsible for the visual records of Rio de Janeiro in the decades from 1810 to 1830, described an everyday scene:

At around four o’clock in the afternoon, one sees the small capitalists arriving from all the adjacent streets to the Palace Square, to sit on the parapets of the dock, where they come to feel the cool air until the Ave Maria (from six to seven in the evening). In less than half an hour there´s no more room.

The Mestre Valentim fountain was inaugurated in 1789 in the place of another fountain, designed by the Portuguese military engineer José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim, that had been erected around 1747. Four decades later, the region of Praça XV square (then known as Largo do Carmo) was restored, along with other construction work in the city, in the areas of sanitation, water supply and attempts to make the city more attractive, that were carried out under the government of Viceroy Dom Luís de Vasconcelos. A new fountain was commissioned to the skilled Mestre Valentim — a black artist, born in Minas Gerais around 1745, also responsible for construction work in the Passeio Público Park and inside several of the churches of Rio de Janeiro. The water came into the spouts of the fountain after passing along the Carioca Aqueduct which is now known as the Arcos da Lapa. And the sea, which had once lapped at its steps, gradually receded with the successive landfills in the region, in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The predominant stone used in the construction is granite. Some details of the stonework are in white gneiss (a type of rock), which contrasts with the grey granite. The prismatic body of the fountain is surrounded by a balustrade – a sort of ‘railing’ – made of stone, which served as a guardrail for people climbing to the top, up a staircase inside the fountain.

The construction is still flanked by two flights of steps that used to lead to the sea, before the successive landfills. They are depicted in various works of art by travellers, such as in this engraving by Thierry Frères, based on the original by Jean-Baptiste Debret. They were unearthed during excavation work carried out in the 1980s and it is once again possible to see the stone steps by the fountain.

As this is a work from colonial Brazil, there are elements that evoke the Portuguese crown. For example, at the top of the pyramid there is an armillary sphere which was an important object in nautical technology during the Age of Discovery.

The Mestre Valentim fountain is one of the symbols of Rio’s Baroque era. It no longer serves the original function of supplying water to the people of Rio, but it is still beautiful and invites today’s passers-by to imagine the Rio of yesteryear.